Bellingham Police Department disagrees with local activists calling for reallocating police budget money

City police are expressing critiques in the wake of national and local movements to re-allocate police funding in Bellingham and on a national scale.

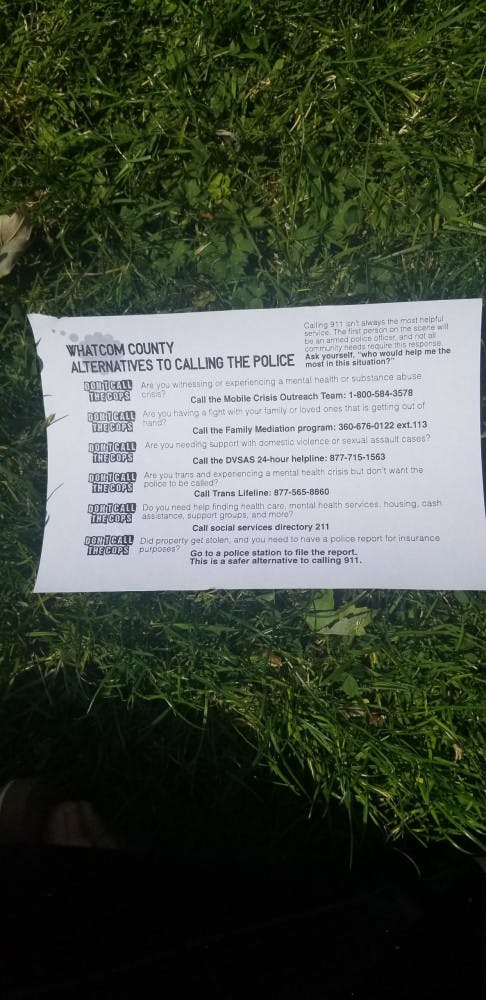

Bellingham residents spoke out Sunday, June 28, at the “Stonewall was a Riot: March to Defund the Police” event, calling for partial defunding of police departments in order to pay for other community resources in the wake of police violence against Black and Indigenous people and people of color.

Bellingham Outreach Officer Jon Knutsen and Public Information Officer Claudia Murphy agree that they need to improve many of the underlying problems that afflict U.S. law enforcement. But they disagree with the method of taking away funding from them to reallocate to other areas.

“The concept versus reality, I think, are two very different things,” said Knutsen. “I understand where people are coming from in their intent to try to get ahead of the issues.”

Outreach officers in the Bellingham Police were once called neighborhood police officers. In the name change press release, Bellingham Police Chief David Doll said they follow community policing, the philosophy of the department. Outreach officers facilitate problem solving, community outreach and organizational change, he said.

Knutsen said he understood the effort to invest in community organizations and mental health services, so people needing help in those areas don’t have to interact with the police.

“I don’t think any officer would argue with that thought process,” Knutsen said.

Knutsen said people believe if communities pull back the police from dealing with many issues like mental health and homelessness, they can invest directly into those parts of the community. But aside from one behavioral health officer position that the Bellingham Police Department funded last year, the department doesn’t have much money going to the staffing and manpower that it takes to deal with the high volume of mental health-related calls that they get, he said.

David Makin, research professor and associate professor of criminal justice and criminology at Washington State University, said improving law enforcement is about starting conversations.

“[I’m seeing this in] areas that are having honest conversations with their community,” Makin said. “Notice the emphasis. Their community. They’re having those conversations around, ‘What should police be tasked with in our community?’”

Knutsen said if the government takes money out of the police budget, he thinks the loss will affect training more than anything.

“My issue is that most people are wanting higher and higher standards for policing, which I’m not opposed to,” Knutsen said. “But the only way to achieve that is through training, which takes money.”

SURJ Whatcom, a local branch of the national Showing Up for Racial Justice campaign, organizes people to fight white supremacy in the county and is in favor of defunding the police. Matteo Tamburini, a SURJ steering committee member, said police training does not address problems that police are supposed to respond to.

“The historical root of policing and the way that it has functioned, even in Bellingham, has been as a tool of racial oppression,” he said.

Makin said conversations between police and communities are about creating trust.

“It’s this idea that if you are honest with your community — you’re honest with what you want in a police service and what your expectations are — you can create a police service that acts on behalf of the community,” he said. “If you lose that trust, then we have to reconfigure what policing looks like. And some areas have made that very drastic change to say, ‘We are closing this police department and we are starting anew.’”

Knutsen said most of the issues he deals with in his job stem from lack of services and resources. He said he talks to community members who are having long-term problems and are frustrated with lack of response from 911 dispatch officers. Knutsen gave the example of businesses being negatively affected by homeless residents in front of their properties, and people using illegal drugs in doorways.

Tamburini disagreed with the police argument that they should have the same, or more, resources.

“You’ve heard the saying, right, that when all you have is hammers, everything looks like a nail,” Tamburini said. “The basic point is that as a society, over the course of time, we have invested all of our resources in hammers.

“We have a variety of problems, mental health issues, homelessness issues, and so on and so forth. And the only tool basically that families have at their disposal is the police.”

Knutsen said he sees people in the Bellingham community latching onto ideas like defunding the police, and he thinks national headlines about the movement are intriguing to them.

“But on a local level, when downtown businesses or residents in a certain neighborhood are dealing with an issue, they all want help and they all want the police to be able to answer their call for assistance and to deal with an issue,” Knutsen said.

Murphy said the services Bellingham residents need when they call the police need bolstering.

Specifically, she said mental health and drug addiction systems in Bellingham need to be rebuilt to provide enough bed space, safety and proper mental health and addiction care. New, accessible diagnostic facilities would be needed, as well as more mental health and social workers. Murphy said law enforcement have to respond to many mental health- and substance abuse-related calls due to lack of proper services.

Makin said the solution was to be deliberate in assigning who deals with these issues.

“It’s about being more purposeful in who is better to handle a specific type of incident or interaction,” Makin said. “What we’ve done over the past 50-plus years is made the police everything to everyone, and that’s unfair. They’re not trained for that, and they can’t be. So if there’s an expert who’s better at handling a particular type of incident, then let’s have that.”

Knutsen said he was getting voicemails from people with very specific problems they wanted handled by the police, and he didn’t think the department would be able to put a dent in those issues if they were defunded.

Tamburini said this was akin to saying they need bigger and fancier hammers, and police military equipment should be decreased.

“If I were someone whose livelihood depended on swinging hammers, that would be my argument as well,” he said. “But really, we need a broader toolset. We need social workers. We need people whose basic training lies in de-escalation.”

Tamburini also addressed police brutality and the safety of the LGBTQ+ and Black, Indigenous and people of color communities.

Knutsen said the department made changes after 2014, when Michael Brown Jr., an unarmed Black teenager, was shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri. Knutsen said the department got body cameras to film and increase officer accountability in police involvement and worked de-escalation into almost every aspect of their training.

He said the Bellingham police use force in 0.4% of calls. He added that the definition for use of force could just mean grabbing someone’s hands and putting them behind their back forcefully because they didn’t comply with orders.

The Bureau of Justice Statistics defines use of force as the amount of effort required by law enforcement to gain compliance from an unwilling subject.

The percentage of local police incidents involving use of force in Bellingham are tracked and reported by the police department.

https://drive.google.com/file/d/18dIgwngRgN4tmjpGcZaIQmZvr8M9LGVb/view?usp=sharing (Table of Bellingham use of force stats)

“I would say most people, from watching the news, have an idea that force happens and is used against the public much, much more than it is,” Knutsen said. “You start dealing with individual cases, and I think that’s where we can make progress.”

Knutsen recommended watching a video project he was involved with that addressed the topic of defunding police.

Murphy responded about the effects of defunding the police and said it was a complex task.

“The allocation of funds is a very complicated process and just because funding is removed from police budgets, will not mean it is re-allocated to [community resources],” Murphy said in an email. “This is a very complicated issue for which any details and planning have not occurred.”

Makin said small, important changes can still be made.

“Part of this movement is asking for some of those changes which do not require re-tooling or refocusing everything we do in terms of policing and public safety,” he said.

Makin gave an example of external, independent investigations of police misconduct, which do not require police defunding.

Another way he said police could reform was by moving some offenses from the criminal to the civil system. Basically, some offenses could mean fines and fees instead of being the responsibility of the police.

“If you’re going to reform the police, you have to narrow what they essentially see,” Makin said.

One example he gave was deprioritization mandates that cities like Tacoma and Seattle have enacted. Police and the community have come together to say they view issues like simple marijuana possession as nonissues that police should not spend their resources on. He said a more controversial example was taking drug possession and use out of the criminal system.

Murphy said it was important to fund community resources like health care and social work, but that it had to be well thought out with a plan in place for how it would be accomplished.

“There is not a law enforcement officer who would disagree with the fact that calls for people in mental health and drug addiction crises are on the rise, particularly in the past five years,” Murphy said. “There is an overwhelming need to bolster both of those systems with billions of dollars federally, as most local jurisdictions are not able to fund the complicated systems needed to properly care for the people in need of these services.”

Murphy said the amount of money that would be needed to prepare a staff that could effectively treat the amount of people in need of care would be staggering.

She said budgets were agreed on at the city level, and departments were only given the amount they could use. Any money removed from the budget would affect services and training.

Bellingham police say they need to reform, not defund — whether by focusing more on training and improving police response to individual cases, as Knutsen said, or rebuilding mental health and substance abuse support systems to improve care for people struggling with those issues, as Murphy said.

“Our training standards are very high, and we have many hours devoted to training to develop the most well-rounded and educated police officers possible,” Murphy said.

Makin said the police service exists to serve the community, and if the community no longer trusts them, the institution has to restart. But that should be very rare, he said.

“It’s so critical to understand that this is not a broken system,” Makin said. “It’s broken in some areas. It’s fractured in some. But it’s also working in a great many.”

Makin said the effects of different ways to distribute funds to police are largely unknown, and to improve, law enforcement needs to get creative.

“You need to have the ability to create experimental conditions,” he said.

Makin said for police and communities to meet in the middle, they need to have a conversation around what each side is willing to give up. He said they need to converse about whether the police are willing to make those types of changes.

“Sometimes both sides can be wrong,” he said. “And someone has to break first. Someone has to say, fundamentally, ‘I recognize the harm that some of our policies and our actions have caused the community. We’re sorry.’ A genuine, ‘We’re sorry, and we want to start repairing it.’”