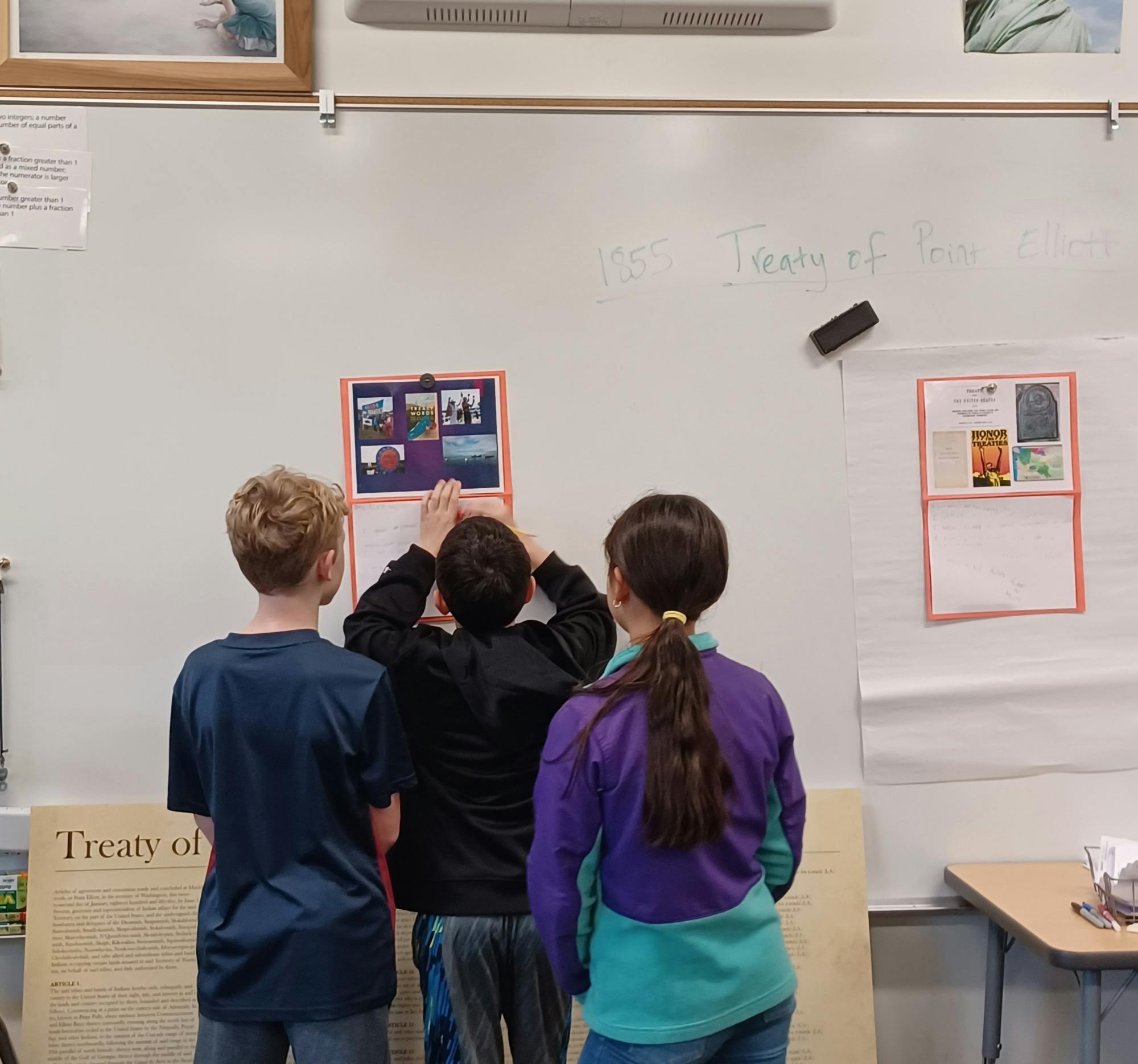

“What do you already know and what questions do you still have about the Treaty of Point Elliott?” asked Kirsten Jensen, an instructional coach at the Bellingham School District, to a class of fourth and fifth graders at Happy Valley Elementary on Nov. 20, 2023.

“It had to do with tribal lands,” said one student.

Jensen marked their response in black pen on the left side of a T-chart pinned to the whiteboard in front of the class.

Bellingham Public Schools District honored Treaty Day for the first time on Jan. 22, 2024, taking the day off from school to commemorate the signing of the Treaty of Point Elliott in 1855, when the Pacific Northwest treaty tribes signed away their land rights to white settlers — but a day off is part of a much larger effort to acknowledge local and regional Indigenous history.

District fourth, seventh and 11th graders took a field trip Jan. 16 to the Mount Baker Theatre for a Treaty Day Film Festival by the Children of the Setting Sun Productions.

Jensen said the 40-minute lesson was designed to spark curiosity and establish students’ baseline level of knowledge. Students made observation and inquiry charts in alignment with Guided Language Acquisition Design, a technique which aims to connect ideas through visual learning.

“The treaty was an agreement that set our communities into a relationship that is central to our ways of interacting,” said Joanna Thomas, the community outreach director for Children of the Setting Sun Productions. “These communities are brought together through that historical treaty, which granted the Lummi Tribe the right to hunt and fish, the right to healthcare and education. So the films are all thematically important to our ways of living.”

Thomas said that students will view a variety of debut short films, including “Sleeping Bear,” an animated nature origin story; “Water Walker,” which explores the resource of water; and “The Sound,” highlighting the challenges facing Indigenous youth.

Bellingham’s tribal curriculum meets the requirements of Washington state’s Since Time Immemorial Act, which mandated teaching local Indigenous culture and history in public schools in 2015.

Washington State Senate Bill 5433 expanded on a 2005 edition of the bill, which only recommended tribal curriculum. It also encouraged regionally specific curriculum, for which students learn about the tribes whose ancestral lands they live, work and play on.

This expansion was thanks to the efforts of late state Sen. John McCoy, a representative and member of the Tulalip Tribes who authored the bill. He died in June, leaving a legacy of education advocacy.

“A story that kind of lit a fire under [John McCoy] was when my twins were in kindergarten in the Marysville School District, they were given a standardized test,” said Angela McCoy, the late state senator’s daughter. “And of course this was written by middle-aged white men in New England. … They would show the boys a picture of an orca. And the boys would say ‘orca, qal̕qaləx̌ič, blackfish,’ but what they were looking for was ‘killer whale.’”

The incident helped John McCoy realize that a state recommendation was not enough; Native curriculum needed a mandate. He also advocated for a regionally specific curriculum that would have permitted his grandsons to use the Tulalip Lushootseed language for “orca.”

“In the tribal language, there’s no difference between language, culture and history,” said Suzi Wright, a retired senior instructor of linguistics at Western Washington University’s teacher training program. She challenged the Western world’s separation of academic disciplines, and emphasized the importance of language for Indigenous epistemology, or ways of knowing the world.

Angela McCoy added that before Since Time Immemorial, schools would often teach Washington students about Navajo or plains tribes. Non-Indigenous students would not learn about their tribal neighbors and Indigenous students would not see themselves reflected in the curriculum.

The Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction’s website includes lesson plans that apply to school districts across the state, such as tribal sovereignty and treaty rights. Regionally specific curriculum emerges from collaboration between school districts and neighboring tribes.

The original bill mandates that school districts “shall collaborate with any federally recognized Indian tribe within their district … to incorporate expanded and improved curricular materials.” By contrast, districts shall collaborate with the OSPI on Indigenous topics that are “statewide in nature, such as the concept of tribal sovereignty and the history of federal policy towards federally recognized Indian tribes.”

The updated bill replaced the phrase “school districts are encouraged to” with “school districts shall” to institutionalize the mandate.

Renee Swan-Waite, a member of the Lummi Nation, teaches a seminar about understanding Since Time Immemorial requirements at Western’s Woodring College of Education.

She helped lead a Whatcom-wide teachers workshop at Sehome High School in August to help teachers design and implement a culturally-appropriate curriculum that meets Since Time Immemorial requirements.

“Somebody followed up with me and put together this incredibly beautiful, fun workshop for her students,” Swan-Waite said. “The students live in Blaine and so it was really about the water, the mountains, who were the first Indigenous people that were there. … They had to write a poem themselves based on 10 questions they had been asked [about the relation between place and people].”

While Since Time Immemorial was primarily intended to educate non-Indigenous students about their tribal neighbors, the bill also helps Indigenous students develop their identity.

Kristen Piel, a member of the Yakama Nation and council member at Western’s Native American Student Union, grew up in the days when Since Time Immemorial was merely a recommendation.

“I definitely was one kid that was taught that Christopher Columbus discovered the United States,” Piel said.

She said her high school history teacher countered Eurocentric narratives, but Since Time Immemorial’s passage helped formalize Indigenous curriculum.

“I definitely would love for them to teach the tribes’ traditions, their teachings, their beliefs,” Piel said. “And not singling each of the kids out and treating them differently. … Having that response of mindfulness and kindness and not thinking of them as objects or things that have disappeared or they think is nonexistent.”

Heather Jefferson, a wellness advocate at the Northwest Indian College, emphasized the importance of the curriculum for Indigenous wellness.

“The [Since Time Immemorial] curriculum mirrors back to us the identity that we recognize, and that’s what we do as human beings, we’re constantly finding ourself in the environment,” Jefferson said. “That cyclical Indigenous teaching of wellness, it helps us to know ourselves better. And our foundation is to know who we are and where we come from.”

Mia Limmer-Lai (she/her) is one of two copy editors for The Front this quarter. She is a second-year environmental studies and journalism student at Western with a minor in honors interdisciplinary studies. In her free time, she enjoys reading books and listening to punk music. You can reach her at mianlimmerlai.thefront@gmail.com.