Late at night on Dec. 24, 2022, chunks of ice slammed into and overtop a section of levee on the Nooksack River, breaching a 200-foot section of the human-constructed river bank meant to reduce the impacts of flooding.

“If it keeps on raining, levee's going to break,” singer Robert Plant of Led Zeppelin bemoaned in the self-titled 1971 album.

And break it did.

With parts of Slater Road underwater, the Marietta-Alderwood community saw flooding almost as bad as in the historic floods of November 2021, according to Paula Harris, Whatcom County River and Flood Manager.

An estimated 18 new cases were added to the work of case managers at the Whatcom Long Term Recovery Group, whose case load had already exceeded 600 after the severe flooding in November of 2021.

The nonprofit started in 2022 after a conglomerate of community organizations realized the desperate need for a long-term aid organization in Whatcom County.

Ashley Butenschoen, the vice president of the WLTRG, started her work after helping her brother’s family escape rising flood waters in Everson in 2021.

“I went in, and I helped, and I got them out,” Butenschoen said. “That night, I helped set up a shelter and run resources out there.”

An image of the breached levee after the U.S. Army Corp of Engineers was able to conduct emergency repairs in January of this year. Damage to the levee on Dec. 24 left parts of Slater Road completely underwater. // Photo courtesy of Paula Harris

The most recently breached section of levee represents only a fraction of the total in the Nooksack area. Parts of the river, like the section from Everson to the mouth of the river in Bellingham Bay, are almost continual levees on both sides, according to Harris.

Levees work to prevent flooding in certain more populated areas, but a surge of water still needs somewhere to go.

“The river moves silt and wood, and if it deposits in a farm field, it's kind of a bummer for the farmer, but it's not catastrophic like if it's somebody’s living room,” Harris said.

Although these levees have benefits, changing the river so drastically also has negative impacts, according to Lt. Col. Richard Knox of the U.S. Army.

When a levee is constructed, the once long and meandering natural floodplain is reduced to one linear bank. A myriad of problems, including loss in habitat and biodiversity, lack of nutrient dispersion and, in some cases, an increase in flood risk are introduced, according to Knox.

Along the Nooksack specifically, this means less habitat and fewer resting places for salmon traveling upstream during spawning season.

“Over the 20th century, we spent billions of dollars on flood control, but flood losses went up 250%,” Knox said. “What happens when you start to build an artificial levee is you start developing right behind it, and you actually increase your [flood] risk.”

Knox’s flood model estimates that a New Jersey-size area of floodplain has been disconnected from rivers in the United States, indicating that we might be getting close to peak levee.

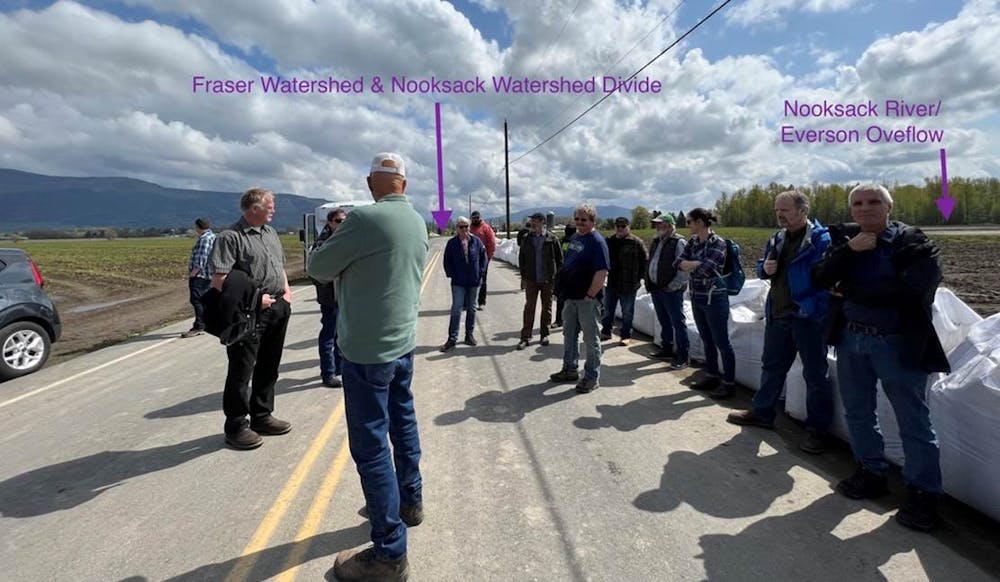

Harris and her team recognized the shortcomings of levee construction and created a conglomerate of stakeholders from across Whatcom County in response. The Floodplain Integrated Planning process, which started in 2017, works to maintain the Lower Nooksack River Comprehensive Flood Hazard Management Plan.

“We get [everyone] from federal officials to farmers sitting at the same table,” Harris said of the FLIP team.

A moveable floodgate to control water flow has been put in place on Duffner Ditch, and another is scheduled to be constructed by 2024 on Cougar Creek, both a result of the FLIP committee’s work. A newer design for a flow split to corral flood water between towns as opposed to into them was introduced during the FLIP process in April.

The billion dollar question, according to Knox, is how to balance river ecosystem function and flood prevention. Levees work to prevent the worst of most floods but at the cost of ecosystem function.

“The future is a time when rivers and floodplains are connected,” Knox said. “People aren’t living in floodplains as much; they’re living above the plain, and we can still navigate in rivers.”

The benefits will be huge, but it's a long road to get there, according to Knox.

One less levee at a time.

Riley Weeks was a city news beat reporter for The Front. She is a senior in the environmental studies/journalism program and is working to complete minors in American Indian Studies and Law, Diversity and Justice. When she's not reporting, Riley loves to hike, bake and read.

You can reach her at riley.thefront@gmail.com.