A comprehensive overview from the 1918 Spanish flu to now

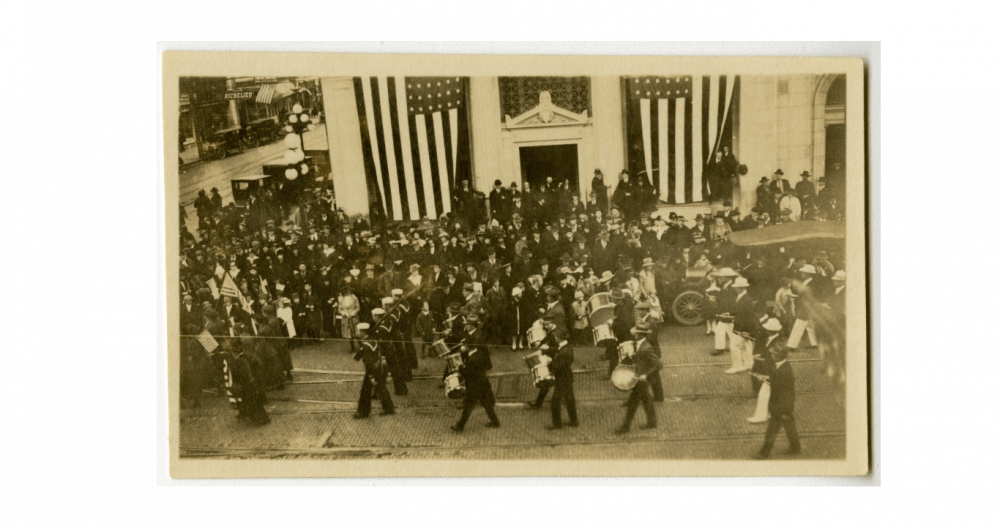

On Nov. 8, 1918, amid the Spanish influenza pandemic, the city of Bellingham Police Force made 22 arrests between 10 a.m. and 6:15 p.m. all for the same reason: not wearing a mask in public.

Two days earlier, The Bellingham Board of Health turned a statewide gauze masking order into local law, and it was to be strictly enforced by police powers, according to meeting minutes from Nov. 6, 1918.

According to Bellingham Police Force arrest records for the month of Nov. 1918, all detainees were released as the order was cancelled. The records do not clearly show how long the detainees were held. By this time, places of indoor public gathering, including schools and churches, had been closed for just over a month, according to Bellingham City Council meeting minutes from Oct. 7, 1918.

“Well, of course then they had to open the stores again, because people needed stuff,” said Jennie Elenbaas, Whatcom County resident who was 26 years-old at the time, in an interview with Kathryn Andersen of the Washington Women’s Heritage Project on July 16, 1980.

“It was so bad there wasn't a family here hardly that didn't have a death in the family.”

Elenbaas said she was unconscious for two weeks and lost all her hair due to the sickness. People did what they could to care for their family members, since doctors were rarely available, she said.

According to an article from The American Reveille — another Bellingham-based newspaper active until 1927 — on Nov. 12, 1918, Mayor John Sells lifted the order to close public spaces on Nov. 11.

Tony Kurtz, Western’s university archivist and records manager, said the Western Board of Trustees at the time initially planned to keep the school closed until the conclusion of the quarter, and reopen in Jan. 1919. Instead, as conditions improved, Western’s president George W. Nash ordered classes to resume on Nov. 18, 1918, after originally closing on Oct. 8.

“I'm not in a position to assess the merits of President Nash's decision in terms of public health outcomes,” Kurtz said. “But it sounds as if state and local officials at the time had lifted the ban against public gatherings, so at least he was acting consistently with respect to the information he had at the time.”

Western’s student newspaper at the time, The Weekly Messenger, remained mostly dominated by news related to World War I until its end, according to archives available on Western’s MABEL platform — a historical collections database of Western and the Pacific Northwest region.

On Nov. 23, five days after the school had reopened, The Weekly Messenger noted Western’s first student death, Anne Ruth Harrison, on their front page. Harrison passed on Oct. 13, according to the article, and the next day The Bellingham Herald said she was the first known Bellingham fatality.

The Herald headline on Oct. 14 read, “First local victim of influenza is summoned.”

Public gathering spaces closed again on Dec. 18, according to the Bellingham Board of Health meeting minutes from Dec. 17, 1918. The order was rescinded at the next meeting, except for closures on dance halls and skating rinks.

The Bellingham Herald reported in an article on Dec. 18 that the police were not enforcing the order on the affected businesses, and owners refused to close as they had not received official orders from the Board of Health, only newspaper reports.

Instead, signs were placed at entrances to businesses warning those who may be sick to keep out, according to the Bellingham Board of Health meeting minutes from Dec. 19, 1918. Guards were also placed at business entrances as enforcement. The Board of Health motioned for the press to notify the public to follow precautions or “the city will be closed tight.”

According to Western Alumni Melissa Mabee’s contribution in the Center for Pacific Northwest Studies’ 2004 Journal of the Whatcom County Historical Society, cases peaked again near the end of December before trailing off into the early months of 1919.

Kurtz said Western’s administrative response during this period mirrors that of more modern day health crises that have occurred since the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-19.

“These were strikingly similar,” Kurtz said. “I think the scale is different today not only due to the much larger size of the WWU community but also the greater mobility of the population.”

Kolby Labree, co-owner, operator, guide and researcher of Bellinghistory with the Good Time Girls — who conduct walking tours in Bellingham to various historical areas around the city — said the COVID-19 pandemic has brought this forgotten-about crisis back into conversation.

“As far as I can tell from [Melissa Mabee’s] research and my own research, it’s so similar to what’s going on right now,” LaBree said. “Arguing about masks, politicians flip-flopping and nobody really knowing what to do.”

Nearly 70 years later, in 1982, Whatcom County health officer Greg Stern completed his master’s degree and was beginning medical school at the University of California, San Francisco just as the AIDS epidemic was beginning.

“Going through [medical] school we didn’t know what it was and how it was transmitted,” Stern said. “We’d be interviewing patients with gowns, gloves and facemasks, taking all of these precautions.”

Stern said at the time all they could do was treat the infections caused by patients' compromised immune systems, as there was no cure.

“There was a lot of fear. We’ve learned a lot more, and that made a big difference,” Stern said.

According to archives available in Western’s MABEL platform, the AIDS epidemic frequented The Western Front headlines from 1988-96.

By Dec. 1989, the Western Board of Trustees had established a “Commission on AIDS Education” that would remain until more was known about the virus, how to treat it and the social response to the epidemic became consistent, according to the Board of Trustees meeting minutes from Dec. 7, 1989.

The Western Front published a four-page report on Jan. 31, 1989, in which Western’s director of counseling and health services at the time, Nathan Church, estimated “probably” 30 to 80 Western students had AIDS. The legitimacy of those numbers are unknown as no official figure of students infected was released.

On May 7, 1991, The Western Front reporter Chris Schneidmiller wrote that 12 people in Whatcom County were suffering from AIDS, and 135 tested positive for HIV, though they noted that many people were not being tested due to social stigma.

In Jan. 1995, the Sean Humphrey house on H street in Bellingham was established as a community home for low-income people living with HIV and AIDS, according to their website. The Sean Humphrey House is still providing these services.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has a comprehensive national timeline of the AIDS epidemic available on their website, here.

Kurtz said measles have also been a consistent battle at Western, with the most intense outbreak beginning in 1994 when the university was forced to cancel campus events and implement large-scale immunization for students and employees.

The Western Front reporters Aaron Dahl and Neely Stratton wrote on March 10, 1995, that the vice president for student affairs at the time, Eileen Coughlin, said that as immunization began the spread at Western was held to 13 cases.

Stern said the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003 never reached Whatcom County, but emergency services were preparing for the possibility.

In 2005, the Whatcom County Health Department established a Pandemic Influenza Task Force, Stern said. The goal was to create a community-wide plan and framework to aid in the response of a future influenza pandemic and assess methods of maintaining critical services, according to a Whatcom County Pandemic Influenza Task Force report for July 2006.

The city of Bellingham received a training grant from the Federal Emergency Management Agency in Aug. 2008, and officials from many Whatcom County jurisdictions attended an emergency preparedness course, Stern said.

Stern said that a unified command team had already been established by the time the swine flu arrived in Whatcom County in the spring of 2009. The command was led by officers from Whatcom County, the city of Bellingham and St. Joseph Medical Center.

Some Western events were cancelled for precautionary reasons, as the university was prepared for any potential outbreak, Kurtz said.

“In Whatcom we benefited from having it as a whole community response,” Stern said.

Greater preparedness in Whatcom County for the COVID-19 pandemic would not necessarily have impacted the spread of the virus the same way it did swine flu (H1N1 flu), Stern said. Impact and spread are mostly correlated with virus severity.

However, Stern noted the absence of federal unifying guidelines, as well as community resistance to measures to slow transmission of COVID-19 have not helped slow the spread.